Andy Ezeani

Tuesday, February 3,2026

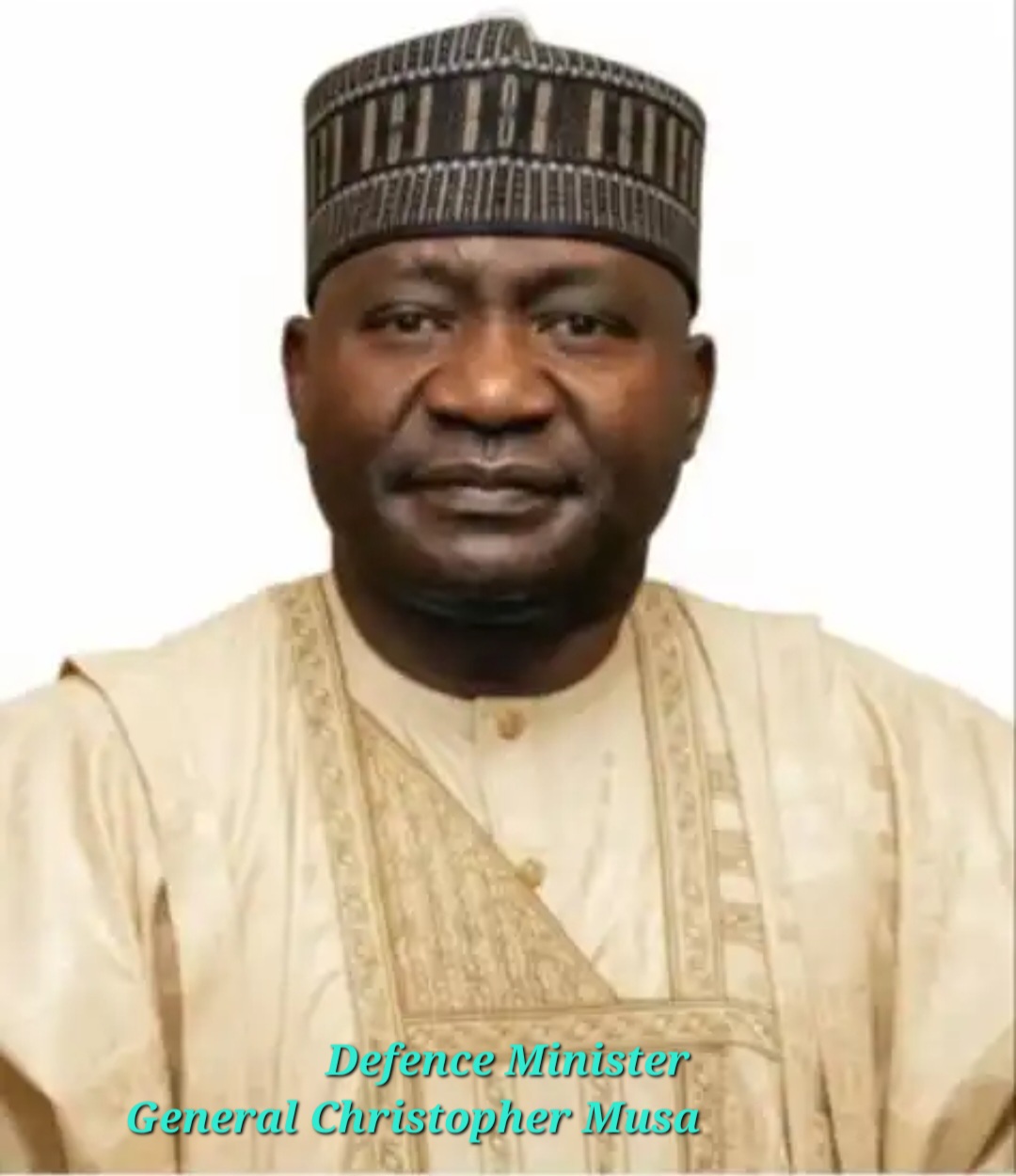

After an initial bout of denials and disinclination to embrace the truth, the Federal Government and the military authorities formally acknowledged early in the year that indeed, there was a plot by some military personnel to topple the Bola Tinubu government in October 2025.

Although the relevant security agencies have reportedly completed investigations into the matter, details of what happened or nearly happened remain sketchy. The coup plot is yet to be appropriated tagged, too. More on that later.

Nigeria and Coup d’état are not strangers to each other. In at least nine instances within a period of 31 years, from 1966 to 1997, Nigeria either experienced full-blown coups d’état, or had a brush with their rustling whirlwind.

Of the nine incidents in reference, at least three were bloody to varied degrees. Some were successful. Others were aborted. One ended up being the butt of jokes as a result of the muddling up of phrases by the manifestly inebriated frontman of the adventure.

In whatever form or shape they came, coups d’état or coup plots in Nigeria always justified themselves, or sought to do so, by waving the shortcomings of the governments they sought to topple.

Cataloging the shortcomings and infractions of governments in power have never been a big deal, anyway. As a matter of fact, that was the easiest part of any such scheme.

Instructively, the leitmotifs of coups d’état in Nigeria have never realised their rosy promises. Indeed, no coup has succeeded, in the long run, to transform the society or lift the lot of the majority to a better pedestal, as promised

It bears noting that coups are only condemned when they fail. Every coup d’état that succeeded found enough disciples who latched on to its lofty promises to amplify its essence.

After nine coups in 31 years, Nigeria ought to have acquired a clear perspective of the nature of military putsch. There should be a definite pattern of their classification. That has not happened.

From what is known about coup plots, the fewer the primary subscribers to them, the better their prospect. Clearly, coups are not organic enterprises. They are not only secretive in nature, they abhor broad subscription. It always boils down to an extremely tight group of like-minded associates often inhabited by a Messianic complex.

Leaders of coup plots always seem to believe that they could change the world by their action.

Thus, it was that on January 15 1966 a group of young officers, reportedly disenchanted with the political crisis that was engulfing the young Republic, particularly in the western Region, staged what has turned out to be Nigeria’s inaugural coup d’état.

How the January 15 1966 coup was executed rather than what its intents were, turned out to be the defining identity of that first putsch.

Six months after the first coup, the second coup followed, a reprisal. Thirty years down the line, eight other coups have occurred in Nigeria with varied levels of success and impacts.

In 1975, a coup toppled General Yakubu Gowon and enthroned General Murtala Muhammed in his stead. The coup was bloodless.

Barely seven months later, on February 13 1976, Murtala Muhammed, who was a key player in the July 1966 reprisal coup and was now head of state, was killed in a coup attempt that did not succeed beyond eliminating him and few other top officers. General Olusegun Obasanjo succeeded Muhammed.

Seven years later, on December 31 1983, the fledgling democratic government installed in 1979 got toppled in another military coup, heralding General Muhammadu Buhari as head of state.

Two years later, on August 27 1985, Buhari was ousted in a palace coup. Enter General Ibrahim Babangida. On April 22 1990, after five years in office, Babangida’s government was jolted by a coup attempt, the face and voice of which was Gideon Orkar.

The Orkar coup, though aborted, was audacious, with far-reaching effect. The putschists actually dislodged Babangida briefly from his official residence at Dodan Barracks, Lagos. The incident precipitated the movement of the seat of the government of Nigeria from Lagos to Abuja.

On August 27 1993, consequent upon the crisis that trailed his annulment of the presidential election of June 1993, Babangida set up an Interim Government, installed Chief Ernest Shonekan, and went away.

On November 17, 1993, less than three months into the interim contraption, General Sani Abacha staged his own coup, brushed aside the interim government, and mounted the saddle.

Four years down the line, on December 21, 1997, Abacha informed the country of a coup plot against him, led by his second in Command, Lieutenant General Donaldson Oladipo Diya with about eight senior officers.

Diya’s initial life sentence was later commuted to a long jail term. A section of the public argued for long that Abacha’s allegation against Diya and his associates was a trump-up charge. A former security assistant to Diya, Major Seun Fadipe, however, confirmed later that, indeed, there was a coup plot to oust Abacha from power. Diya was indeed culpable.

Coups are military-political gambits, with extreme prospects for their masterminds. They succeed, they gain political ascendance. They fail, they die.

Coups d’état are never community projects. They remain risky individual undertakings. No military coup is classified, therefore, by the ethnicity of its masterminds. Except one. For obvious political purposes.

January 15,2026, marked 60 years anniversary of the first coup d’état. For reasons that verge on desperation and obvious lack of common sense, some elements around the Tinubu presidency took up a puerile campaign to remind anyone who did not know, or was not yet born by then, that the January 15 1966 coup was an “Igbo coup”.

The laboured effort was pathetic. The belief that if you hurt the Igbo, you gain those who will distance themselves from them is a most curious and obtuse political strategy for any candidate in search of friends.

Only last year in 2025, General Ibrahim Babangida had pooh-poohed the tag of the January 15,1966 coup as “Igbo coup”, dismissing such classification as wrong and dishonest.

What Babangida said, Major Wale Ademoyega, one of the participants in the 1966 coup, had written about in his book on the adventure of the young majors in early 1966. All that, however, count for little to those who believe that whipping up sentiment against the Igbo offers Tinubu a political profit. But does it?

As the government grapples with the confirmed October 2025 coup plot, over which no less than 16 military officers have reportedly been arrested, only one of who is said to be from Osun State and the rest from the northern part of the country, the shallow propagandists around the corridors of the presidency have a small task at hand.

How do they classify this one? A northern coup? Just as the Diya coup that had eight top Yoruba military personnel should go down in history as a “Yoruba coup”?

But coups have shown themselves not to have ethnic colourations. They should be left, even in memory, as what they are; a game ambitious military officers and military ideologues play.